Putting History Online: Some Considerations

Online exhibitions and digitized collections provide many new ways to collect, author, and share history. Planning these digital projects involves many considerations, some new, but most familiar. Digital history is still history, after all, and I would argue the best digital projects follow many of the same planning procedures as analog ones, even if specifics vary.

Putting Mission First

The first step for any public history project, even before considering technology, should be to determine the project’s purpose and set out its intended audiences and outcomes. What is the theme of an exhibition? Is digitization intended for preservation, accessibility, research, or to provide resources for educational materials? How does the project fit with the institutional mission?

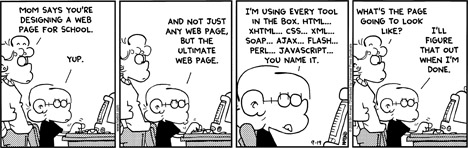

These are basic questions, but it is vital that digital history projects stay focused on real human outcomes. When museums and archives rush toward a new technology without having a clear idea of how it furthers their mission, the “gee whiz” impact of new media and the dictates of the platform can distract from these institutions’ core historical materials and programs. Technology should be a tool to support the institutional mission and project goals, not an objective in itself.

Assessing and Allocating Resources

All digital history exhibits and collections require resources like funding, staff time, and actual content to put online. Digital projects may also require hardware and software resources such as scanners, server space, and content management systems. Getting an early grasp on what resources are already available and what still might need to be acquired will help the project planners determine if they can comfortably carry out their goals in house, if they need to look for additional grants or outside collaborators, or if they need to scale back their ambitions.

Choosing a Platform

There is no one-size-fits-all technology for digital history. Choosing the best software platform to implement a project requires finding platforms with features that match a project’s specific goals, as well as evaluating costs, support, ease of use, system requirements, and compatibility with different data formats.

In my own digital projects, I utilize free software whenever possible. Free software is not necessarily free of cost, but it gives users the freedom to view, modify, and redistribute changes to the software source code. This allows users to create and share new features, improving the software for everyone. The open availability of the software code further ensures that projects are not locked into a single vendor who may suddenly alter features or drop support. Free software for history exhibits and collections includes specialized tools like Omeka, Open Exhibits, Collective Access, and CollectionSpace, as well as general-purpose platforms like WordPress, Drupal, and MediaWiki which run much of the modern web.

Interface Design & Making the Most of the Medium

Although digital projects should reflect an institution’s broader mission, they shouldn’t necessarily resemble the institutions’ offerings in other media formats. The advantage of going digital is its promise to open new ways to access and interact with collections. Web users are accustomed to hypertext and the ability to choose their own path through material. They are adept at searching, scanning, and skimming to find items of interest without always pausing to read large blocks of text. They are frequently eager to save discoveries to their own collections or share them with social media contacts. The best online history exhibits and collections facilitate rather than interrupt these use patterns, while still aiming to effectively communicate exhibit themes and historical context.

Project Timeline and Life Cycle

Scheduling for a project needs to take several elements into account. Exhibits must be researched, written up, and designed. Digitization requires time for both scanning and copying materials into digital formats as well as for creating metadata and perhaps correcting or marking up text. The underlying media platform also needs time to be installed and configured.

It is also vital to consider how long into the future the project will be supported. Software and digital formats are constantly changing, as evidenced by the steady stream of updates to our personal computers and mobile gadgets. A digital history project meant to be useful over the long haul needs resources to handle future maintenance updates and changing storage needs. The data and metadata format for the project must also be chosen carefully. Proprietary formats might offer helpful specialized features, but open format standards make it easier to transfer data between software platforms and ensures that the key to deciphering the format remains available even if the original tool for the format disappears.

Security & Backups

Museums and archives aim to carefully protect their physical collections, and the same should be true of digital resources. Even if a project involves no sensitive records and is meant to be fully publicly accessible, the online world presents risks ranging from simple bugs and hardware failures to malware and hackers who might try to turn a project’s computing resources to their own ends. It is crucial to distribute backup copies of digital materials in multiple locations, to keep software up to date, and to practice simple security procedures like using strong administrative passwords and systems to track who has access to make changes to the project.

Reflective Practice and Project Assessment

Bringing a project from conception to implementation is bound to involve making compromises and adjustments to the original goals — such changes are a healthy sign of creative flexibility. Just as when creating physical exhibitions, though, it is helpful to keep an eye on the big idea and plan time to deliberately reflect back on the project purpose to avoid getting thrown too far off course by the pressures of time, resources, and technologies.

It is also increasingly critical to provide a way to assess how well the project meets its intended outcomes. Digital projects make it relatively easy to track usage statistics and patterns. This information can help inform future projects and demonstrate program effectiveness to donors and stakeholders, allowing museums and archives to continue improving their digital efforts.

One Response to "Putting History Online: Some Considerations":

Josh, I couldn’t agree more with your point that museums should make the most of what the web has to offer. I’ve seen so many online exhibitions that just seem to be digital replications of traditional exhibitions, or words and images on a screen. I think the best online exhibitions are those that recognize the unique possibilities of the medium, which means building a hyper-textual, interactive, and/or customizable experience. Of course, this could be a challenge for museums and other historical institutions that lack the staff capacity and technological infrastructure to devote to such a project. On the other hand, it’s also possible that attempting to do too much at once could result in a jumbled mess. But it’s worth considering how the web and new media can potentially transform how public historians present history and engage with audiences.

Comments are closed.